It is unknown when the first passenger aircraft services took place in the United States, but one of the earliest recorded instances was in 1913.

Sular Christofferson transported passengers between San Francisco and Oakland harbours by hydroplane.

Another early instance was in 1914 when passengers were carried from Tampa and St. Petersburg, Florida by a Benoist airboat.

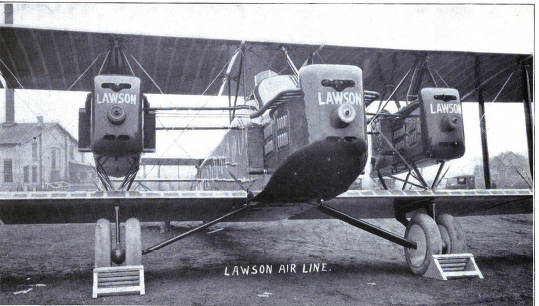

One of the first steps in commercial aviation was the development of the multi-engine airplane by Alfred W. Lawson after WW1.

The Lawson C-2, built in 1919, was created specifically to carry passengers.

Related Article – Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC): 4 Things You Need To Know

The plane was somewhat a failure; the price of military aircraft was much cheaper, so the C-2 was not worth the price to buy.

Lawson went on to build the L-3 and L-4, both larger aircraft that were capable of carrying 34 passengers and up to 6,000 pounds of cargo.

Problems arose once again, this time after the plane crashed on its first flight, causing the development of the L-4 to come to a halt.

In 1920, a Florida entrepreneur by the name of Inglis Uppercu started to offer international flights from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba.

The service was eventually extended to other parts of the country, and there were flights between Miami and the Bahamas, New York and Havana, and the Midwest states of Cleveland, Ohio, and Detroit.

Uppercu’s Aeromarine Airways’ “airborne limousines” were going strong until one crashed off the coast of Florida, resulting in the death of four passengers and the company going out of business in 1924.

One of the big moments in commercial aviation came when mail began to be delivered by air.

In the early 1900s, the common means of transportation for mail was by railroad systems connecting cities in the country.

The first official airmail flight took place in 1918, and it rapidly increased after that.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

By 1925, the U.S. Post Office was delivering 14 million pieces of mail per year by airplane.

This new mailing method was especially popular among those in the financial industry who wanted a quicker way to mail checks and documents.

Airmail was eventually transferred to private companies from the government, and the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925, known as the Kelly Act, was sponsored.

The act was the first big step in creating the private U.S. airline industry.

Soon after the establishment of the Kelly Act, the Post Office began to give out contracts to private companies after they bid on certain routes.

This continued to expand for almost a decade, and the private companies went on to become the major transportation players in commercial aviation.

Henry Ford was awarded the Chicago-Detroit and Cleveland-Detroit routes after obtaining the Stout Metal Airplane Company in 1925.

He went on to establish the Ford Air Transport Service, and he developed the “Tin Goose,” an all-metal Ford Trimotor.

Ford was involved in the mailing industry for a short three years before going back to manufacturing.

The government created a national aviation policy in 1926 after President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board headed by Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan.

Morrow was not supportive of directly subsidizing airlines.

Instead, he wanted the government to fund a national air transportation system, which was taken up and recommended by Congress in the Air Commerce Act of 1926.

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

The act gave a lot of authority to the Secretary of Commerce, who then had a role in the development of air navigation systems, air routes, the licensing of pilots and aircraft, and investigations surrounding accidents.

The Kelly Act was eventually amended by Congress, and the government carriers were paid based on the weight of the mail they were carrying.

These changes played a big role in the financial success of the airlines.

Research and training were also going through changes in the 1920s, especially with the establishment of a foundation by Harry Guggenheim.

His foundation aimed to develop flight instruments and educate aeronautical engineers at universities.

Besides his foundation, Guggenheim was involved in funding the Western Air Express, which included a $180,000 experiment to know if airlines could profit solely from passenger transportation.

The experiment failed after they were not able to make sufficient money without the subsidies.

The Western Air Express experiment was one of many that failed.

This changed in May of 1927 when Charles A. Lindbergh flew solo to Paris.

After the successful flight, investors were excited, and aviation stocks tripled between 1927 and 1929.

This helped propel the commercial aviation industry forward.

Even with all of the developments in commercial aviation, passengers could still get to their destination faster by train in the late 1920s.

There were too many limitations with planes compared to trains, which were able to travel through mountains, could run at night, and did not have to land and refuel like aircraft.

On top of that, trains were more comfortable than planes.

Passengers in the air dealt with loud noises, forcing them to put cotton in their ears, and the cabins were un-pressurized.

Despite all of the uncomfortable and limiting aspects of air travel, air travel grew in popularity.

The number of airline passengers in the United States went from less than 6,000 in 1926 to about 173,000 in 1929.

The passengers mostly consisted of businessmen, who increasingly had their tickets paid by employers.

The Ford Trimotor 5-AT, introduced in 1928 and produced through 1932, was popular among most U.S. airlines.

It carried up to 15 passengers, and there was one still being used all the way up until 1991 in Las Vegas.

The aviation industry continued to grow with the creation of jobs, airports, warehouses, aeronautical schools, and new technology.

The first instrument navigation package was used by U.S. Army lieutenant James Doolittle in September 1929.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

Research at the Full Flight Laboratory, established by Harry Guggenheim, helped create an extremely accurate barometer, a radio direction beacon to help land, and a Sperry artificial horizon and gyroscope.

These allowed Doolittle to fly 15 miles without having to look outside his cockpit, revolutionary for air travel.

Even with all of the advancements and excitement in commercial aviation during the 1920s, the part of the industry dealing with passenger-only routes failed to make a profit.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that these airlines began to make financial gains.